After three weeks the raging flames of national pride have finally abated.

Not only does life in Quebec deprive the American sojourner of his precious Diet Wild Cherry Pepsi – available so far as I can tell only in the U.S. – but it subjects him to yet another day of national pride: St. Jean Baptiste Day, June 24. Now some might find it odd to celebrate the life of a rigorous ascetic and martyr with public drunkenness but this curiosity was soon surpassed by the strangeness surrounding Canada Day, July 1. On Canada Day the residents of Canada celebrate gaining their nominal independence from Great Britain by flooding over the border into the U.S. to buy cheap goods and eat at American restaurants. But despite all of this, the manner in which the Canadians celebrated their national holidays struck me, for one thing was missing. No where in the proceedings was divine blessing recognized, invoked or besought. This of course stands in stark contrast to the frequent references to God and divine approval of the American project that so pepper American celebrations on July 4. It’s hard to imagine the Toronto Blue Jays stopping every evening mid-seventh inning to sing “God Bless Canada.” It would be … untoward, i.e. un-Canadian.

As I mentioned last year while reflecting on all of the God talk surrounding Independence Day, we Americans have an interesting (perhaps even schizophrenic) theological relationship to the notion of America’s pseudo-divine character. On the one hand we note the genocide against native Americans, the enslavement of Africans and the internment of Japanese Americans (someday soon we may ma add “and the torture of captives”), but we usually follow these quick recognitions of past wrongs with a too quick, “But despite all that we’re still the best country in the world. I mean, look at all of the people who want to come here to work and study.” Our flaws, we tend to think, are mere hiccups along the way. What really matters is the fact that we have been selected by God to do something of world-historical importance. When our ancestors sailed here (ignore the cargo holds full of rum, guns, and slaves) in search of religious freedom they began a project of realizing God’s plan. We were to be a nation set apart, a beacon on a hill, a calm voice for truth and freedom amid the raging seas of history. With this godly charge the American experiment was launched and so our history (the stuff written in text books) has usually included the notion of American Exceptionalism: We aren’t like other nations. The same rules don’t apply to us. Truly a recipe for disaster!

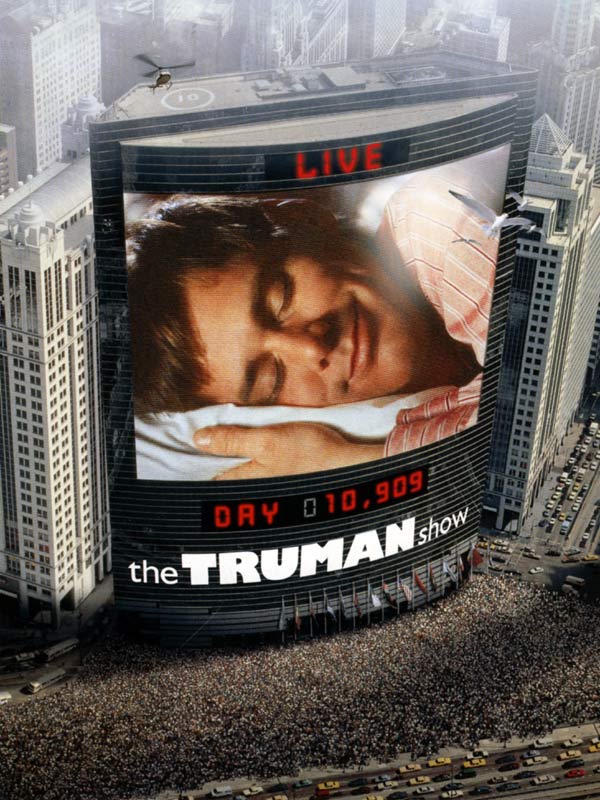

As I post this blog the July 4 holiday is fading from memory, but I hope to take a couple of lessons from Independence Day 2009 regarding the workings of our churches. There is, I think, a common, perhaps universal, human desire to which American Exceptionalism gives voice; the wish to be somehow special. I don’t mean special in the way that our mommies mean it when they pack our lunches and send us off to school with a reminder that “We’re special.” No, I mean special in the sense that the very rules and laws of nature that apply to other people, other religions, other social groups, and other nations, these rules and laws do not apply to us. We are the exception. We’re exceptional. We want to believe that the quotidian lives of other “ordinary” people are somehow less significant than our own. It’s a kind of solipsistic fantasy in which many of us secretly long to be the Truman of our own Truman Show. We may even have a hunch that somehow, among Earth’s 6 Billion plus inhabitants, we are meant for something more. “So carry on mundane mortals. Go about your little lives with you little countries and your little wars. I/we have a larger task. We’ve been selected by God to carry the flag of history forward. We cannot fail.”

This isn’t a political blog, so as usual I’m thinking about what happens when this same turn of mind enters our congregations. What happens when we begin to think of ourselves as exceptions? How many of us think of our churches, denominations, and congregations as somehow above the fray? I know that I wrestle with this habit all the time. As I sit in committee meetings discussing policies, I am not thinking to myself, “We need these procedures so that I do not get too far off track.” No! most of us think of setting up checks and balances so as to keep the other guys from doing wrong. It’s kind of like the speed limit – it’s there to protect me from all of those other bad drivers. But this particular danger is elevated when we turn toward religious concerns and communities.

We all know that we will encounter disagreements and possibly even jerks at our workplace. The Office is funny precisely because so many of us can relate. But when we enter into our religious communities we sometimes expect the basic rules of human nature and social interaction not to apply. Is there a kind of force field surrounding the sanctuary that keeps mean-spirited folks from entering? Does this force field magically transform us from the people who work in factories and offices with gossip and politics to sugar plum ferries of niceness and harmony? Forgive the dripping sarcasm, but we all know that this isn’t the case. We know – even if we seldom prepare for it or admit it to ourselves publicly – that we are the same sinful, sometimes mean-spirited, sometimes petty people on Sundays as we are during the week. And when we ignore this or rush past it, we miss out on an opportunity for better understanding ourselves and our communities.

Here, I think, is where the comparison to American Exceptionalism is helpful. I LOVE the U.S.A. and I love and appreciate it more and more the longer I live outside of it, but I am also coming to see us and our history through the eyes of non-Americans. I am coming to see that we are NOT exceptional. The same rules of human nature and laws of physics apply to us. We are subject to the larger ebb and flow of history as are other countries. America is unique. It’s special. It’s wonderful and wonderfully full of cheap Diet Wild Cherry Pepsi. But its people are still people. Its policies are still the policies of one country among many. Our flaws and foibles as a people and a country are real and are not invisible because we sometimes choose to ignore them in lieu of a larger truer vision of ourselves. And most importantly, when we fail to take ourselves seriously as subjects to the same history and habits as other nations and peoples, we miss a profound chance at gaining a better understanding of ourselves. American Exceptionalism robs us Americans of a more nuanced vision of ourselves and lessens our ability to make intelligent decisions about how we ought to govern ourselves and what kind of role we should play in the world.

Our congregations are in constant danger of misunderstanding themselves in a similar manner. Sociologists have spent decades developing powerful tools and rigorous methods for studying the ways in which people interact. We know why social groups forms, what keeps them strong, and what forces threaten to destroy them. We know how important it is for a tightly knit social group to maintain certain similarities and how easily these binding properties can be lost. We know what good leadership looks like and we can explain with impressive accuracy the kinds of leadership that will and will not work in specific scenarios. However, all of these explanations and tools require that we admit at the outset that people are people no matter where they live and that social units behave in predictable ways both inside and outside of religious contexts. In other words, we are best able to understand our religious communities when we do not expect that our communities will be exceptional, when we admit that we remain fully flawed humans even when we cross the church threshold.

For many of us this is a very difficult admission to make. Because we’ve found love and comfort in our churches and congregations we sometimes come to think of them as immune to the forces that govern other social groups. Because we were raised in a church or came to a church as an outsider but found a warm welcome we might expect these institutions to somehow hover above the rough seas of social strife. So it can be very hard to admit that the church or congregation we love is not exceptional just as it is often difficult for those of us who love America to admit that our nation is not exceptional. But when we step back from the particulars and try to gain a “God’s eye view” we are able to see the desire to think of oneself or one’s community as exceptional for what it is: human pride. It’s the kind of pride that God laughs at. It’s the kind of pride that hurts us and prevents us from fully acknowledging our creaturely statues and need for grace. It’s the kind of pride that we desperately need to get over in our national consciousness and in our congregations.

The Liberal-Evangelical project is dedicated to the idea that we Evangelicals are fully flawed humans, and our congregations are gatherings of flawed people who are in no way exceptional. Liberal-Evangelical Exceptionalism is a kind of idealism. It recognizes that the ideal community of Jesus-inspired radically inclusive love is a goal that we have not yet (and probably never will) perfectly realize. We fail to realize it because we are human. We aim for it because have accepted the challenge to follow Christ’s Gospel. But we recognize that it is extraordinarily difficult to bring to fruition because we are unexceptional.

Not exactly bumper sticker material is it?

“Liberal-Evangelicalism, Christianity for Unexceptional People.”