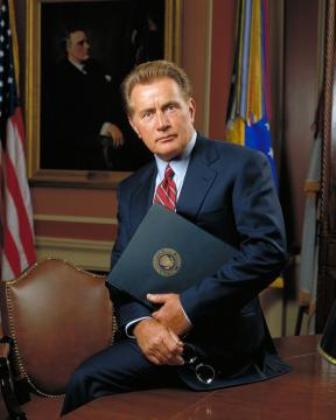

This past week we watched as President Obama spoke to the Muslim world and raised, yet again, the prospect of peace in the Middle East. Many of us are praying that the new administration finds a way to accomplish what so many others have failed to do, but we’re skeptical. I’m not yet an old man, but even I remember five other American Presidents trying and failing to bring the Palestinians and Israelis to a peaceable compromise. I’m not necessarily a cynical man, but I don’t imagine that the tag team of Obama and Hillary will manage it this time either. I used to love NBC’s The West Wing, but as soon as President Bartlett managed to create a peace settlement, the entire show lost credibility!

And yet, despite my frustrations, I continue to pray for peace along with millions of other Muslims, Jews, and Christians. We pray and hope even as we doubt. We’re frustrated and exasperated in part, because it all seems so petty; these fights over who owned what strip of land six decades ago. The original protagonists are largely dead and gone, so the remaining fighters are stuck fighting a kind of absurd proxy battle, waging war over hurts and harms that they themselves experiences only vicariously through the stories of their parents and grandparents. Certainly, there have been other outrages and attacks on both sides since the 1940s and 1950s. Yes there has been plenty of death and violence to keep the old wounds open. But surely (and this suggestion comes so easily to those of us looking at the conflict from a distance) the price paid in lives and limbs has not been worth it.

“Peace! Peace!” We want to cry. “Just knock it off! Enough already.” But of course it is not so simple. There is an epic battle being waged not only between the Israelis and the Palestinians, but between two different conceptions of the fight in the Middle East. What then is our first calling? Are we called first to be peacemakers or are we given a divine mandate to fight for justice.

As the prophets Jeremiah and Ezekiel noted in different times and slightly different language, “Peace, peace,’ they say, when there is no peace.”

One of the most difficult skills to develop as a member of a congregation is the ability to understand and empathize with the moral rigidities of your fellow congregants. Personally, I’ve always found it easier to deal with people who I disagree with, but who are relatively flexible and pragmatic, than those who invest almost infinite worth in a position and refuse to budge – even when I agree with their position! Sometimes laughingly we call these folks the”true believers.” They are the ones who plant the flag of truth in a particular molehill and declare it a mountain of justice. “We will not have a female minister!” “Under no circumstance will we ever serve anything but fair-trade coffee!” “Every service must include one hymn!” “The biggest category of our budget must always be Outreach!”

These rigid folks exist on both sides of almost every issue, and in some ways they serve an important roll. They help to preserve institutional memory and keep us tethered to our heritage. But too often we find that their various inflexibilities block the way forward and prevent needed change, so we try to work around them, giving in where and when we can, only to wake up and find that our church has become a stitched together collection of entrenched interests. My best illustration of this point dates back to my days in youth ministry. Down in the bowels of the church – where so many congregations stick the teenagers hoping to keep them from damaging the nicer parts of the building – there was a large room that served a single purpose. Once a year for about 8 hours a group of retired women would gather in that room to hot-glue together bows, beads, and candles, in order to make ornaments to sell at the Christmas fair. When their work was done, they would pack up their supplies and seal them in the room again, not to be disturbed for another 364 days. It was a huge room, a wonderful space that could have been put to use throughout the year, but heaven protect the unsuspecting youth minister who dared to suggest that a smaller closet would suffice for storing Christmas supplies! I quickly understood that serious entrenched interests were at stake and withdrew my request to move the Christmas items. Clearly this particular molehill was not worth the carnage that was sure to ensue if I persisted.

I wonder if Carter and Reagan and Bush and Clinton and Bush and now Obama felt and will feel something similar as they try to negotiate with the entrenched interests in the Middle East? Please, do not misunderstand me. I do not mean to make light of six decades of death and pain. Of course the analogy between the church closet and the Golan Heights is superficial. But as I watch this latest instantiation of the push for peace in the Middle East I see a common psychological thread. It is easy to cry for peace when looking in at a problem from the outside. But to the insider, I wonder if the cries for peace do not seem wholly superficial.

In his Letter from the Birmingham Jail Martin Luther King Jr. criticized the white southern clergy for telling him to slow down and wait for justice. From the perspective of the white clergy King looked to be an agitator, starting trouble where none was necessary. Surely there were those who looked at Evangelical abolitionists as trouble makers and pot-stirrers. “Peace, Peace” so many people cried as John Brown burned armories and worked to free slaves. So as I look to the Middle East with cynical eyes I am unsure as to what I should really be hoping and praying for. Should I pray for peace or should I pray for justice? Can we have one without the other?

I won’t be playing an active role in the Middle East peace negations but I can try to be a better peacemaker in my church, and sometimes this may mean working to understand and tolerate the people who refuse to make peace. Just as one person’s trash can occasionally be another person’s treasure – half the furniture in my Boston apartment was found on the side of the road – the superficiality that I dismiss as a trifle may be of utmost importance to someone else. Conservatives may look derisively at the “hopeless hippie” who works tirelessly to get the church to recycle the cups from coffee hour. Liberals may scoff and titter at the “old curmudgeon” who petitions the minister to keep the organ. Some roll their eyes when their fellow Christians insert announcements into the bulletin about upcoming rallies for immigrant worker’s rights, while others roll theirs at those who organize yet another Lenten prayer group.

Because there are limited resources, both temporal and financial, every church cannot pursue every ministry, so we fight. And when we fight, how quickly we dismiss that which the other side holds dear. “Come now,” we argue, “let us have peace. If you will just put away your petty demands we can end this fight and live together.”

“Come now,” they argue in return, “we only want what is right and just. Put away your petty demands, recognize what is rightfully ours and let us have peace.” All the while there is no peace.

So when I watch events in the Middle East over the coming months and I see other people fail to make peace time and time again, I am going to try to redirect my cynicism. I’m going to try to see in the intransigence of my fellow parishioners a heart longing for justice. I’m going to try to see in their demands – especially those demands I see as petty – a desire for what is right. Just as I pray for peace in the Middle East and sincerely hope that something may finally come of it, I will work not to become a cynical peacemaker in my own much smaller world. I will try not to shout down or dismiss other people’s calls for justice. It may turn out that they are right. It may turn out that in my church, just as in the Middle East, the path to peace must be build on a foundation of justice.