Is there anything new to be said about Christmas?

I’m not the only one asking this question this week. Trust me; your ministers are desperately seeking an answer to this question themselves as they prepare Advent sermons, Christmas eve sermons, Christmas eve early service children’s talks, Christmas day sermons and, in some cases, homilies for the late night Christmas eve carol sing. Think about all of the words that they have to generate; what makes matters worse they are intimately aware of what they said last year (even if most of us aren’t). They are panicked about saying something new – something even more profound than last Christmas.

But for roughly 2000 years they had to preach the same story with the same cast of characters; so the chances of coming up with something new, or of seeing some nuance that will yield profound insights, is pretty slim. The good news for these harried servants of God is that for once it doesn’t much matter what they say so long as they stick to the general script. The story can do the work for them. A couple of shepherds and kings from central casting, a baby doll, a couple of bales of hay and some of the kids in paper wings and you have all you need for a successful Christmas story.

Someone once said that the only intelligent thing one can say upon seeing the Grand Canyon for the first time is “wow,” because anything else interrupts the sublime experience and gets in the way. Something similar holds for the nativity. The story itself carries what philosophers might call the “semiotic burden,” in other words; it doesn’t need much interpretive nuance to have an intense impact. It stands on its own. Maybe we do the most by just staying out of the way and giving sermons that amount to “Wow”.

Anyone who follows this site and Le Blog has noticed that I’ve been silent for about a month. I’ve been buried in Christmas and Thanksgiving preparations like many of you, but I’ve also been working with the authors of Lost in the Middle? to prepare the manuscript for the forthcoming companion volume Found in the Middle. It’s been a helpful experience for me. Rereading a manuscript that I’ve seen come together over the months, I find myself immersed in the world of liberal-evangelical theology. But on the far end of the experience I’ve come to understand the Christmas story in a different way.

Wildman and Garner have spilled a lot of ink and worn out even more shoe leather in the service of congregations so they understand theology and the Bible in the way that a carpenter understands his tools. They don’t romanticize the tasks of making sense of Christology or interpreting the Bible to contemporary congregations. They don’t set out to create theological edifices and to generate cunning apologetic schemes. In fact, their work reminds me of nothing so much as the hardnosed dedication of a working parent whose daily fight to fill stomachs and provide warmth and comfort to children is driven not by careerism but by the desire to do good work so that they bread that is earned is honest and well deserved.

I mention this point only because I’ve been listening a bit too much to talk radio and cable news lately: I know that the culture wars rage around Christmas. Olbermann and O’Reilly fight a nightly battle royal over the “war on Christmas” and the struggle for or against the phrase “Happy Holidays.” Honestly, I find this entire thing a bit sad, as if the fact that corporations trying to appeal to the broadest possible shopping demographic shouldn’t be expected to use the vaguest possible holiday greeting. Does this really dampen the spiritual and religious value of Christmas more than the fact that Christians celebrate the birth of a homeless messiah by maxing out their credit cards? Oh, but the secular vs. religious battle over the Holiday/Christmas season isn’t actually the most vicious fight that takes place this time of year. The real fight, the one that I truly mourn because is rips open old wounds in the Body of Christ, is the fight between the “Nativity Litmus-Testers” and the “One-Size-Fits-All Social Justice Crowd.” I think that most of us know these groups even if the names I’ve just given them aren’t familiar.

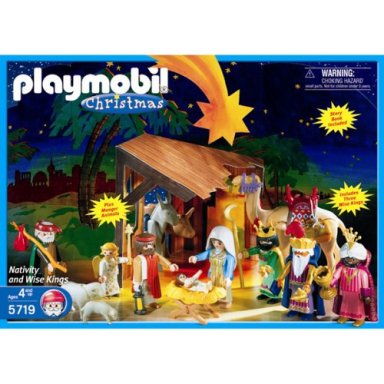

Nativity Litmus-Testers: These are the people who refuse to put the Three Wise Men in the Nativity scene, insisting that they didn’t show up until Jesus was a toddler. They argue about the exact date of Christmas and try to make a case using computer models and astronomic data – when would an extra bright star have appeared? They are the Litmus-Testers because for them no Christmas sermon is complete and no preacher is to be trusted until they get a clear cut answer to the question of what exactly the virginity of Mary entails. Did the Holy Spirit contribute DNA? Was the Christ child some sort of clone? For this crowd the bare factuality of the birth stories are what is important. Who exactly were these kings from afar? Of what wood was the manger constructed? Was the infant Christ conscious of his divinity even as a newborn?

One-Size-Fits-All Social Justice Crowd: These are the people who get squeamish at the whole Christmas story, just as they do come Lent and Easter. “Why do we need all this Jesus talk?” They skip the pageant and the carol sing, opting instead to restock the food pantry and take out the recycling – knowing all the while that their social service is far more important to the cause of peace and justice than songs and (let’s be honest) naive stories about donkeys and angels and babies. The only sermon that pleases them is one about how we all ought to be working more diligently toward universal health care, ending hunger and homelessness, and riding the world of dangerous weapons. When they hear a Christmas homily they judge the preacher solely on how deftly she or he can move beyond the messy details of Bethlehem and get to the real meat of social justice.

These two groups, I hope, represent the outlier positions for Christians. At one end are those for whom the Christmas story is to be read as one would read a police blotter: “The facts ma’am, just the facts.” At the other end are those who would love, like President Jefferson, to snip out all the bits of the Bible and the Christian tradition that don’t pertain to progressive social values and rational uplifting discourse. Most of us do not live out on these margins and tend to approach the Christmas story in a more moderate fashion.

I think that most Christians treat the Nativity scene as a kind of symbol, recognizing that there potentially are two errors that we should avoid. The first danger is that we take the symbol so seriously that we forget to ask about its meaning. We get stuck on the symbol itself, like we frequently get stuck on the letter of biblical texts, and fail to catch the spirit. The other danger is that we rush past the symbol in such a hurry to get at the deeper and truer meaning that we forget that we cannot access God without symbols. Our Pentecostal sisters and brothers constantly remind us of this through their worship in tongues (though many of us never stop making fun of them long enough to learn from them): When we try to get past words and language and access God without mediating symbols, we arrive at something we cannot comprehend.

We should ask: what does the Christmas story mean? But we cannot ask this question if we become obsessed with getting the details right, or if we insist on “getting past” the story. There is a balance to be struck here between obsessive fixation on the details of the narrative and willful disdain for the aesthetic form the story takes.

Many of the work-a-day ministers, the blue collar (dare I say it!) “Joe the Plumber” type preachers strike this balance intuitively in large part because they allow the varied needs of their congregations to function as the chief guidelines in their sermon preparation. Most ministers of a liberal-evangelical bent – ministers who tend toward the moderate middle because they sense that their congregants are not terribly interested in the pitched positions on either end of the culture wars – tend to approach the Christmas story with an appreciation that is quite elegant, even if it is seldom articulated. They understand the childlike quality of the story – the quality that allows the nativity figures to be mistaken for toys by every two year old. They know that they have to preserve something of this simplicity as their sermons unfold. (How exactly is a toddler supposed to understand that the donkey and sheep belong in the nativity but the triceratops and stegosaurus do not?) But they also rightly intuit that there has to be some difference between the recounting of the story during children’s time and the interpretation of the story for adults. What can one say about this little tableau that won’t spoil its simplicity but will speak to the complexities of contemporary life?

Well, you didn’t really expect an answer did you?

Ok, I’ll give it a shot.

The chief danger here, as I see it, is that we over-interpret the story, stretch it too far and try to make it do too much. We shouldn’t mangle the Bethlehem narrative to make it fit our theology. We can talk about homelessness, and poverty, and economic justice – they were heading to Bethlehem for a tax census! But let us not use the story to push such a specific agenda (one I heartily agree with) when this may be the only sermon some people hear all year or at least until Easter. At bottom the story is about incarnation, but even that word is a bit too metaphysical, too loaded – what does it mean for God to become “carne”: MEAT! If we’re not careful we’re locked once again in ancient debates from Chalcedon, Nicea, and Trent.

We should allow our native religious instincts to take over here. Many, if not most of us, will approach the Creche with awe and silence. We intuitively lower our voices and change our body language. We sense that somehow God is closer here at this moment and in these symbols. As preachers and ministers we can push this feeling and try to put words to it. We can talk about God’s omnipotence and stress the fact while we may feel God’s presence on Christmas, it is an ever present reality. This statement would be true. But I wonder whether we might not simply do best by doing less. Can we find ways to allow people to soak up God’s presence with minimal extrapolation and interpretation? I think many of us need this opportunity. Perhaps we need this chance more than we need to know the Who, What, When, Where, and Why of divine presence. Folks in your congregations this Christmas season may simply need a reminder of the ACTUALITY, the THISNESS of the divine presence. Perhaps the most elegant thing we might do from our pulpits and lecterns this Christmas season is trust the Christmas story to do for and in people the very thing the narrative describes: allow God to become a reality in the world. If we think of our task not as one of preparing a memorable and new sermon, but of removing impediments to the story, then our jobs are a bit easier this year, and we might be truer to the real needs of our congregations.

I won’t be preaching at all this season, so I have no “skin in the game” as the saying goes. But for those of you who are, try going out on a limb and trusting the symbol, the Christmas narrative that we have woven together over the centuries from bits of Matthew, Luke, and Isaiah. As someone who will hear at least three Christmas sermons this year, I ask only the following of those who will address me. I’m more than a little worried about our country and world. I have very little confidence in our economic future. I have been buried in travel and shopping preparations and have had little enough time to sit with the Gospel stories and allow the birth of Christ to sink in this year. Please, don’t distract me from the story. Push me deeper into it if you can, but don’t be the kind of speaker who stands by my elbow at the edge of the Grand Canyon and prattles on about erosion and geography. No doubt you have considerable oratorical skills or you wouldn’t be offering a Christmas sermon: martial them carefully; use them sparingly; find a way to help connect me with the story and be in the presence of God and just say “Wow.”