Get Started

Chapter Summaries

Basic Sociological Principles

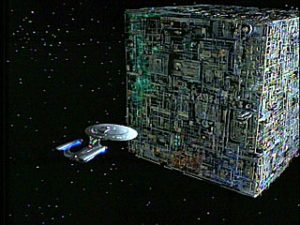

With all of the different denominations and styles of worship it is easy to forget that most of us need the same basic things from our churches. Our churches must be both institutions that help us encounter God on a regular basis and they must be places where we can feel at home. Theologians concentrate their attention on the first need, while sociologists study the later. Luckily, these needs are not mutually exclusive, and there are many churches where people find ways of engaging God and feeling settled in their surroundings. Sociologists, however, have noticed that just beyond the safety of our church communities lurks the danger of chaos. When trusted ministers betray their parishioners, when once welcoming congregations turn hostile, when these things happen we face the prospect of losing our anchor. Disorientation threatens and the metaphorical sky threatens to come crashing down. This state of bewildered anxiety sociologists call anomie and it threatens us at our core, whenever our deepest convictions and expectations are challenged. This fear of homelessness and chaos is one of the factors that prevents us from acknowledging some of the deep disagreements that permeate our churches.

Chapter 10: Core Message Pluralism

Understanding the threat posed by anomie as outlined in the previous chapter, enables us to face what may be the biggest challenge to moderate congregations: core message pluralism. Liberal and Conservative Christians not only disagree about peripheral issues and questions of style. At bottom, they tend to have very different ideas about the core message of the Gospel. For many congregations, both Liberal and Conservative, the solution to the challenge posed by core message pluralism within the Church is to form individual churches where a single core message is clearly presented. This actually works to create tightly knit communities and keep anomie at bay for many parishioners, but for moderates this solution leads to disenchantment as their probing questions are shunned. However, there are church bodies that work to make room within their congregations for core message pluralism. Too frequently, however, these churches do so by ignoring deep disagreements. Moderates often sense these deep-seated differences, but are hesitant to articulate them out of fear that unearthing core differences might lead to open disagreement and perhaps even hostility. Thus, on both ends of the Liberal-Conservative spectrum there are tightly knit churches with a crisp and articulate version of the Gospel, while in the middle there are churches with a mix of Evangelical and Liberal impulses, who are afraid to probe deeply and expose their own pluralism for fear of upsetting the fragile balance that they have achieved.

Chapter 11: The Curious Social Strategy of Liberal-Evangelical Christianity

Human institutions are fragile. We desperately need them, so when they are not working we worry about tampering with traditional forms and losing them entirely. In spite of this fear, there are a growing number of churches that are intentionally setting out to embrace a precarious social strategy. These Liberal-Evangelical churches are intentionally embracing core message pluralism, even if it goes by some other name. Liberal-Evangelical Christians reject the simple portrayals of the Gospel on the Left and on the Right, though they recognize that a simple core message can yield social cohesion. They also reject the bland moderation of churches that refuse to probe too deeply for fear upsetting the precarious social balance. Instead, Liberal-Evangelicals opt for the difficult adventure of embracing core message pluralism openly and honestly. They embrace the challenge of running against the sociological odds and live in the hope that Christian love is powerful enough to hold a community together even as its diverse members embrace different versions of the Gospel. Thus Liberal-Evangelical congregations hope to stand as a witness to the inclusiveness of Christ’s love.

Introduction

The good news for those wishing to build strong communities is that sociologists and theologians know what works. Love works. When we feel loved, we feel safe and bonded to those who love us. When we feel bonded to other people, most of us will love those people in return. This mutuality of love reinforces itself and strengthens the community.

The bad news is, while we know that love is powerful, we also know with painful certainty that love has practical limits. We are unable to live up to the ideal of universal love, but instead limit ourselves to loving our own nation, tribe, family, children, or even only ourselves. In theological terms our stunted capacity for love is a function of sin. As sinners we do not love as we ought, and therefore are not loved as we long to be loved by others.

Given these painful limitations, it is amazing that humans have sometimes managed to build strong communities. Many of us belong to loving communities and know the warmth and joy that comes with such belonging. The tragedy here is that these communities almost always develop strong internal bonds by severely delimiting membership. In other words, we know how to build strong communities even in a sinful world: limit membership to those who share our central beliefs and values. Within these boundaries love can flourish and people can feel a deep sense of belonging.

Most of us can see the problem here. As moderate Christians we are uncomfortable with communal boundaries that seem arbitrarily and cruelly narrow. Following Jesus’s own example, we long to build radically inclusive communities without sacrificing the sense of security and belonging that exists in more exclusive groups. What is more, we intuitively sense that love is the key, but have grown tired of naive calls for universal love and cheap togetherness. We want the best of both worlds. We want a strong community, but an inclusive community. And we do not yet know how to make that work.

Get Busy

Exercise

In the far left column below is a list of groups, each of which make use of different social strategies for forming close bonds, reinforcing common goals, and creating cohesive group identities. In the second column, make a list of the internal and external forces or motivations that drive or compel the group to remain unified. In the far right column list several specific unity-preserving strategies these groups enact or behaviors in which they engage. Some members of your study group may belong to groups of these kinds. Take some time to share your experiences with one another, paying particular attention to the things that your group does to build social bonds that are particularly successful. Several boxes have been completed as examples

| Group | Internal and external pressures toward unity | Unity-preserving strategies or behaviors |

| College Sororities/Fraternities | Wear matching clothing so as to be identified with the group | |

| Veterans of Foreign Wars | A need to be around people with common experiences | |

| Trade Union | ||

| Political Party | ||

| Military Unit | ||

| Extended Family | Annual family reunions | |

| Basketball Team | Competition from other teams | |

| Professional Office | ||

| Nation | ||

| Married Couple |

Discussion

In a moment of honesty and transparency, Chapter 11 warns us that “the liberal-evangelical church must run against the sociological odds” (page 154). This means that many of the sociologically effective strategies that were listed in the far right column are not available to us as liberal-evangelical congregations, despite the fact that internal and external social pressures similar to those listed in the middle column remain.

Take a few minutes as a group to go back over the particular strategies in the far right column and think about which of these seem to violate the spirit of radical empathy that pervades moderate Christianity, or undermine the stress that liberal-evangelicalism puts on Christ-centered radical inclusiveness.

We seem to be playing with fire, or at least with matches. We are committed to diverse congregations because we know that we must provide a witness to Christ’s example of overflowing love. We must resist the tendency to flock together merely with “our own kind,” and instead make the strenuous effort of building deliberately diverse congregations. And we must take up this challenge without falling back on the time-tested strategies of uniformity through enforced conformity, the demonization of others, or the expulsion of dissenters. It seems as if we are being asked to do the impossible. If this really the kind of community Jesus Christ had in mind? Can God’s love really overcome the sorts of human differences that routinely destroy the unity of other groups?

Get Caught Up

Homework (to be completed prior to group meeting)

The internet has given us access to thousands of different church websites from all around the world. This week we are discussing “mismatched gospels.” In preparation for this discussion take some time during the week to do a little exploring on the internet.

Pick a state, city, or region of the United States with which you are unfamiliar and use a large search engine to locate several church websites in that area. (Yahoo Local and Google Maps work particularly well for this exercise.) On each church website try to locate a creed, statement of faith, covenant, or statement of key beliefs. Sometimes these are difficult to find; other times there will be a simple link to “What We Believe.” Make a note of the manner in which these different churches try to summarize and present the Gospel in a condensed form.

If you take care to select different kinds of churches (fundamentalist, liberal, evangelical, mainline, orthodox, etc.) then you ought to notice several important differences in the summations of the gospel. Be sure to bring your findings with you to share with the discussion group.

Homework Discussion (during group meeting)

This week’s homework asked you to bring in a few creeds, faith statements, or confessions that you found on church websites. Take some time to share your findings with one another. You may also want to consider collecting and arranging these statements into some kind of order.

It is likely that many of you found statements about the source and proper interpretation of the Bible. Many of you also likely encountered some very specific language about the purpose and meaning of Jesus’s death and resurrection and the role these play in human salvation. Some of you may also have found statements about current political issues like the definition of human life and marriage or Jesus’s stand on issues of social justice and poverty.

It is important that we remember the role the statements you collected play in the lives of these churches. It is highly unlikely that these confessions or creeds deal with trivial issues like the color of the church’s newsletter or the salaries of the staff. These statements tell us what the churches in question find most important, so when we discover diversity in these statements, our discovery is not superficial. Christians genuinely disagree about the core of the Christian message.

Chapter 10 of Lost uses the phrase “mismatched gospels” to emphasize that, while the eternal Gospel of Jesus Christ may be one, there are many different versions (gospels) that make claims on the hearts and minds of contemporary Christians.

- Can you imagine a closely knit church in which different gospels coexist?

The manner in which we answer the first question sets us off on either one of two paths.

If we answer “No – you can’t imagine a closely knit church in which different gospels coexist – then the following questions about which core message is right become important.

- What options does a church have for dealing with core message pluralism, assuming that sometimes people with a different gospel will be in the pews?

- If a church finds that more than a few of its members have a different gospel, can or should a church split be avoided?

- What authorities or procedures might you use to decide whose version of the core message to accept?

If we answer “Yes – you can imagine a closely knit church in which different gospels coexist” then questions about setting boundaries on core message pluralism come into view.

- Knowing in advance that strong communities require some minimum consensus on values and message, if a church decides to try to live with core message pluralism, where will it draw its boundaries?

- If a church finds that more than a few of its members have a gospel that falls outside of the limits the church has set, can or should a split be avoided?

- What authorities or procedures might you use to decide where to draw and how to enforce the boundaries?

Regardless of the answer we give to the first question “Can you imagine a closely knit church in which different gospels prevail?” core message pluralism in the Christian Church is a reality that we must address. Embracing core message pluralism and striving to maximize tolerance does not free you from the need to draw some boundaries. But drawing firm boundaries and minimizing tolerance does not escape the reality of pluralism. How then should we live the Gospel and make it known while acknowledging the practical reality of multiple functioning gospels?

Get Scriptural

Bible Reading: Joshua 4

1 When the whole nation had finished crossing the Jordan, the LORD said to Joshua,

2 “Choose twelve men from among the people, one from each tribe,

3 and tell them to take up twelve stones from the middle of the Jordan from right where the priests stood and to carry them over with you and put them down at the place where you stay tonight.”

4 So Joshua called together the twelve men he had appointed from the Israelites, one from each tribe,

5 and said to them, “Go over before the ark of the LORD your God into the middle of the Jordan. Each of you is to take up a stone on his shoulder, according to the number of the tribes of the Israelites,

6 to serve as a sign among you. In the future, when your children ask you, ‘What do these stones mean?’

7 tell them that the flow of the Jordan was cut off before the ark of the covenant of the LORD. When it crossed the Jordan, the waters of the Jordan were cut off. These stones are to be a memorial to the people of Israel forever.”

8 So the Israelites did as Joshua commanded them. They took twelve stones from the middle of the Jordan, according to the number of the tribes of the Israelites, as the LORD had told Joshua; and they carried them over with them to their camp, where they put them down.

9 Joshua set up the twelve stones that had been in the middle of the Jordan at the spot where the priests who carried the ark of the covenant had stood. And they are there to this day.

10 Now the priests who carried the ark remained standing in the middle of the Jordan until everything the LORD had commanded Joshua was done by the people, just as Moses had directed Joshua. The people hurried over,

11 and as soon as all of them had crossed, the ark of the LORD and the priests came to the other side while the people watched.

12 The men of Reuben, Gad and the half-tribe of Manasseh crossed over, armed, in front of the Israelites, as Moses had directed them.

13 About forty thousand armed for battle crossed over before the LORD to the plains of Jericho for war.

14 That day the LORD exalted Joshua in the sight of all Israel; and they revered him all the days of his life, just as they had revered Moses.

15 Then the LORD said to Joshua, 16 “Command the priests carrying the ark of the Testimony to come up out of the Jordan.”

17 So Joshua commanded the priests, “Come up out of the Jordan.”

18 And the priests came up out of the river carrying the ark of the covenant of the LORD. No sooner had they set their feet on the dry ground than the waters of the Jordan returned to their place and ran at flood stage as before.

19 On the tenth day of the first month the people went up from the Jordan and camped at Gilgal on the eastern border of Jericho.

20 And Joshua set up at Gilgal the twelve stones they had taken out of the Jordan.

21 He said to the Israelites, “In the future when your descendants ask their fathers, ‘What do these stones mean?’

22 tell them, Israel crossed the Jordan on dry ground.’

23 For the LORD your God dried up the Jordan before you until you had crossed over. The LORD your God did to the Jordan just what he had done to the Red Sea when he dried it up before us until we had crossed over.

24 He did this so that all the peoples of the earth might know that the hand of the LORD is powerful and so that you might always fear the LORD your God.”

Reflection

The book of Joshua is relevant because it tells of Joshua’s work to forge a bonded community and primitive nation out of loosely organized nomadic tribes. One of the ways Joshua’s people formed communal bonds was to distinguish themselves from outsiders by avoiding foreign religious practices. They established and maintained their communal integrity by shunning other gods.

This week we take up an earlier chapter. In chapter 4 Joshua and the Israelites have just crossed the Jordan River, reenacting their miraculous escape from Egypt more than forty years earlier. Having arrived at their destination, Joshua pauses to erect a memorial of stone. Interestingly, he sends one member of each tribe to select a stone, so that each tribe will have a stake in the memorial. The purpose of the memorial is made explicit: it will cause future generations of children to question their parents about what happened at this place, and it will provide an opportunity for parents to recount the story of the Jordan crossing. The point of the stones is to preserve the common story!

We know that one of the ways to form a tightly knit community is to emphasize the differences between those who belong and those who do not. Drawing these boundaries stresses the contrast between an in-group and an out-group and creates a natural incentive within the group to care for one another. The result is cohesion and the preservation of a distinctive group identity.

Loving communities do not emerge solely as a response to external pressures and the demarcation of boundaries. Loving communities must be further strengthened by internal forces of compassion and shared experience. Joshua’s story emphasizes the important role that these internal forces play. If all Joshua desired was a loose confederation of tribes that could defend themselves against external forces, then he could have created such a confederation based solely on the social forces of boundary demarcation, self-preservation, and fear of outsiders. But the book of Joshua does not describe merely a convenient military alliance. Its central aim is to describe the first tentative steps toward nationhood taken by the wandering Israelites. Thus, the book of Joshua tells us about the ways in which they began to generate a communal narrative and self-understanding. The process took centuries, as the books of Joshua and Judges both show, but eventually it worked quite well.

The importance placed on a common central story throughout Joshua and much of the rest of the Hebrew Bible should alert us to the challenge that lies ahead. When we acknowledge the reality of core message pluralism and take on the task of building an inclusive Christian community despite these real challenges, we do something radical. We run against the sociological grain of most of world religious history. The Christian Gospel is interesting enough and powerful enough to support many different interpretations, so there are many different versions of the Gospel that serve as narratives for different churches and Christians. The challenge inherent in core message pluralism is to allow these genuinely different versions of the Gospel and the people who hold them dear to exist side by side with one another in community and love.

Get Practical

Case Study

We can recognize the reality of core message pluralism, frankly acknowledge the challenges it sets for building tightly knit Christian communities, and still decide to go forward against the sociological odds. However, as we move ahead with Christ-centered radical discipleship and Christ-inspired creative inclusiveness, we will still find it necessary to mark some boundaries and draw some distinctions. As we noted in our discussion of the previous chapter, our aim as moderates is to maximize tolerance while still maintaining strong social bonds within our communities.

Our desire is analogous to that of a farmer who wants to carry as much produce as possible to market, but has only a single basket. She wants to fit as much produce into the basket as possible without straining the basket so much that it weakens the sides, splits, and is no longer able to carry anything.

Sociology gives one set of rules for what is likely to work in this situation. Jesus set out a more aggressive and idealistic vision, asking his followers to love one another in such a way that the rest of the world could see that God’s love was strong enough to overcome ideological and theological disagreements, cultural and personal differences. The following case study highlights this challenge.

In a medium sized town two churches sit alongside a river. During a particularly rainy summer the river floods its banks and destroys one of the churches.

The surviving church is a thriving mainline congregation with a passion for social justice, political advocacy for antidiscrimination laws, and supporting the local homeless population. As they look down river at the members of the other church picking through the wreckage of their building they decide to make a radical offer. They will extend an invitation to the ministers and parishioners of the other church to join them for a year, until they can salvage their property.

Down river the members of the now waterlogged fundamentalist church stop their cleanup efforts to have a meal and pray. Bravely they make jokes about doing better than Noah and his family did, even while worrying quietly about the direction that God would have them go. As they eat sandwiches they notice that a delegation from the liberal church up river has arrived with dessert. They offer profuse thanks, but truly cannot believe what they hear when the minister of the other church offers for them to join the liberal congregation for a year. They take this offer as an answer to their prayers.

Six Months Later: Pastor Dawson of the mainline church has agreed to meet in private with a group of parishioners from his congregation. After some initial pleasantries they move to address a growing problem. They are glad that as a congregation they came forward to offer aid to another church in need. They are proud that the minister of the fundamentalist church has been given rent-free office space in their building. They are glad to serve as a transitional location for many of the ministries offered at the other church. They even feel oddly blessed by some of the small inconveniences that come with sharing a building and worship service like scarce parking, a less tidy church kitchen, and unfamiliar faces at coffee hour. However, they are seriously worried and even offended by some of the practices that the other church has brought with them.

Karen, one of the concerned parishioners, is a doctor and teaches at the local medical school. She tells her minister about her concerns with what her young daughter has been hearing at Sunday school. The third grade class has been reading some of the stories in Genesis and several of the children and one of the teachers from the fundamentalist church have been emphasizing the literal six day creation of the world. Karen’s daughter knew from some of the books she reads with her mom that the earth is millions of years old. When she said this, however, some of the children made fun of her. Karen no longer feels like she can send her child to Sunday school as long as one of the teachers from the fundamentalist church is there.

Mark is a long time member of the church and helps with church scheduling. He lives nearby and so frequently comes to church on weeknights to let groups in and to lock up when meetings end. Lately, he has noticed that several of the groups meeting at the church – groups that used to meet at the church down the river – seem to have disturbing purposes. One group he encountered was working on a voting guide for upcoming state elections. Mark read some of their materials and noticed that they were supporting conservative candidates, many of whom Mark deeply distrusted. On another occasion he closed up after a group of men who had been meeting to pray and study the Bible, but from what Mark overheard the group was for men who were “recovering homosexuals.” Mark’s sister is a lesbian and Mark dearly loves her and her partner and does not feel comfortable that the church is hosting a group who would think of his sister and her family as sinful or sick.

Finally, Leslie, the associate minister of the mainline congregation spoke. Pastor Dawson was surprised to hear from Leslie in this context because he worked with her every day and thought that they had an excellent working relationship. Leslie admitted that she had been hesitant to speak on this issue because initially she was very much behind the idea of reaching out to those who had lost their church home due to the flood. However, over the past several months she has grown less and less comfortable with the situation. Leslie knew that the fundamentalist church had never had a female minister. As she investigated their beliefs more fully she discovered that they did not even allow for the possibility of female leadership. Women in that church were only permitted to act as choir directors and Sunday school teachers for children. She noticed that the members of the fundamentalist church tended to avoid her when socializing and also noticed that many of them were absent on the Sunday last month when she preached and served communion. She no longer felt like the church was a spiritually safe place for her and admitted to Pastor Dawson that she was considering resigning.

Everyone at the meeting emphasized that they thought that they church had made the right decision in inviting their neighbors to join them as the damaged building was repaired. However, they felt that they were losing their church and thought that some rules and boundaries had to be laid down if they were to continue to thrive as a community. Pastor Dawson was stunned, and as he drove home that night he was at a complete loss about what to do.

Discussion

Pastor Dawson must decide what to do about the remaining six months. Once the other church has been repaired his fundamentalist guests will return to their own building. Until then he is left with the difficult challenge of leading an extremely diverse congregation. He now leads a congregation with several mismatched gospels!

Pastor Dawson has a wide range of options available to him. He can ask the members of the fundamentalist church to leave. He can convince his own members and staff to grin and bear it for six more months.

- How would you counsel him to act?

- How might the notion of core message pluralism help Pastor Dawson make sense of his situation and explain it to his membership?

- Imagine a scenario in which Pastor Dawson talks to his own members and staff about the idea of “core message pluralism” and they come away heartened and with a better understanding of their situation. How might he broach the subject with the members and staff of the other church?

Recognizing the reality of core message pluralism and heeding the call to maximize tolerance and build moderate congregations does not necessarily entail doing away with all boundaries and distinctions. Where might Pastor Dawson and his congregation need to define boundaries?

This case study presents a scenario in which a biologist and surgeon (Karen) is worshipping at a church where a creationist is advocating creationism and in which a member (Mark) who fully welcomes his sister’s lesbian partner into his family helps manage a church building where anti-homosexuality groups meet. In real life such juxtapositions are rare, in part because most Christians choose congregations that reflect their own values. By means of extenuating circumstances our scenario puts these people together in one church–and in some sense, isn’t where we imagine that Jesus Christ would want his followers, together in one church? Is there any strategy that might enable the building of a healthy congregation from such diverse components? If not, at what point do we risk “breaking the basket?”

For Further Thought

Get Going

Chapter 10 of Lost in the Middle? argues that core message pluralism is the central challenge of liberal-evangelicalism. We serve and worship one God through Jesus Christ, but when pressed to explain the detailed significance of Jesus’ life or crucifixion and resurrection we often give different answers. We have different views on the right use of scripture and church organization. We are a tremendously diverse bunch and that diversity is frequently disconcerting and confusing and sometimes downright frightening.

We have choices. First, we can deny our diversity by ignoring the reality of core message pluralism. This, however, is a fear-driven response and one that most of us will, we hope, be able to move beyond.

Second, we can recognize the reality and persistence of core message pluralism. For many of us, the mere acknowledgement of the doggedness of diversity may be a considerable accomplishment. In this case, we will have to find ways of coping with our diversity.

Finally, we can decide to move beyond coping strategies, which in some sense bemoans diversity even while choosing to acknowledge it, by embracing core message pluralism and appreciating the unique opportunity it affords us.

As liberal evangelicals it is not often that we have the opportunity to pioneer cutting edge evangelism techniques, but core message pluralism gives us such an opening. By building loving and inclusive congregations where moderate conservatives and moderate liberals are welcome, where the Gospel of Christ is preached without demanding rigid doctrinal conformity, and where we refuse to worship solely with others like ourselves, we rise to the challenge of evangelism: others will see our love and tolerance and know that the love of God in Jesus Christ has enormous relevance to the challenges of everyday life.

Closing Prayer

Lord Jesus we speak to you today in humility, unsure of ourselves and our words. We know you and love you, but do not always know how best to describe you.

We share an experience of your presence and love in our lives and the life of our church.

We share a desire to keep you at the center of our community. We want our church to prosper and grow in love. We want our community to be stronger, our relationships healthier, and our witness surer.

Give us confidence and courage to speak of you. Help us find ways of talking about you and sharing your love without demanding that others use the same words or express our exact message.

Share with us some of your love for our differently minded sisters and brothers. Cause our patience and humility to grow. Hold us together in your love, even as our words and actions push us apart. Heal our hurts and wounds and make us whole.

Amen