Honestly, the most enjoyable part of writing this occasional blog is coming up with the headlines. I get a chance to make bad puns and employ some acerbic word play. There is of course no war on Boxing Day, any more than there is a war on Christmas or Easter or Lag B’Omer (ask a Rabbi about that last one). These alleged wars all stem from a growing concern among many practicing Christians, especially in the United States and Canada, that the sacred holiday of Christmas, and to a lesser extent Easter, are losing their religious character and being watered-down. Retailers who say “Happy Holidays” and light displays without nativity scenes are all tagged as sure signs that we are “losing the war” for Christmas.

I’ve touched on this topic before and obviously, we are at the moment nowhere near the Christmas or Easter seasons, so this may seem like an odd time to address the issue, but it’s actually the perfect moment for reflection for two reason. First, the fact that we are now entering the muggy months of summer means that we are far enough away from the big Christian holidays to get some emotional perspective i.e. there is no danger that Bing will start crooning “Away in a Manger” over the radio as you read this and except for our neighbor two doors down (You know who you are!) there are no Christmas lights in sight. The second reason pertains to two holidays that Americans are unlikely to know much about, but retain considerable emotional weight here in the frozen wastes of Canada: St. Jean Baptiste Day and Canada Day.

The first thing you (speaking to the non-Canadians here) have to remember is that Canada never had a war for independence from the British crown. The Queen is still on the money and is still the technical head of state. So Canada Day celebrates the founding of the country, but there is no distinct and final moment of independence, no defiant John Hancock or heroic battle charge. The Quebecoise on the other hand, lost a famous battle for independence on the Plains of Abraham just outside of Quebec City back during the war that Americans call “The French-Indian War.” So their national day of celebration is St. Jean Baptiste Day, where they celebrate the feast day of their patron saint.

Just to make matters more interesting, these two holidays are celebrated one week apart, Canada Day following St. Jean Baptiste Day by 7 days, and the iconography of the two days draws a clear distinction. The red leaf folks speak English, drink Molson and Coke and wear red. The blue flower folks speak French, drink Labatts and Pepsi and wear blue. Were this all there was to it, then it would be harmless fun akin to Yankees/Sox, Lakers/Celtics, or Cowboys/Everybody in the NFC East. But back in the day (and I’m being intentionally vague here about the timeline) it didn’t stop at harmless boosterism, because the two holidays were not only distinct in their iconography, they were religiously differentiated. Ethnicity and Religious affiliation determined which of the two holidays your family celebrated and as you can imagine this led to considerable tensions between the French-Catholics and the Anglo-Protestants over the years.

We have a good friend who grew up in a part of Quebec called the Eastern Townships. These are small towns along the Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont border that are fairly affluent and largely Anglo-Protestant. She, however, was from a French family and she tells about being followed home and harassed by drunken men and teenagers on Canada Day, even as she admits that similar things likely happened every summer on St. Jean Baptiste Day. The religious and ethnic undertones of the celebrations (along with the cheap beer) emboldened the less savory characters to harass and sometimes assault their neighbors and vandalize their property. Thankfully, these kinds of religiously and ethnically motivated outbreaks of violence are now few and far between. Why? Because of the successes of secularism i.e. the war on Boxing Day!

Secularism has many faces and manifests itself differently in diverse cultures, but one of the undoubted benefits of secularism in North America is that religious holidays have, by and large, lost their potentially hateful edge. Yes, this sometimes means that Easter Bunnies outnumber Easter vigils, and more people can name the 12 reindeer than the three wise men, but it also means that some of the uglier manifestations of religious and ethnic zeal have been reigned in as the appeal of the holidays have broadened and their association with particular practices and groups has waned. For instance:

for centuries Jews in Christian countries were dreadfully afraid of the Easter season and the Passion plays that took place on Good Friday. These reenactments of the Gospels were often followed by vicious pogroms and looting, a practice that still rears its head from time to time in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Republics of central Asia. Western Secularism may mean that fewer butts are in the seats for Easter services, but Jews now feel much safer to show themselves in public the Friday before Easter.

Saint Patrick’s Day violence is now largely due to drunken frat boys who’ve decided to be Irish for a day – though green plastic top hats are noticeably absent in Dublin! In decades past, Saint Patrick’s Day was a time when Irish Catholics in both Northern Ireland and the large cities on the eastern seaboard of the United States would vent their collective rage against their Anglo-Protestant enemies both political and economic. Let us not forget the anti-Irish Nativist movements that were so powerful in America in the 1800s. Secularism worked to undermine the anti-Catholic hysteria that flooded the American press at that time and thus lessen the ethnic and religious undertones of Saint Patrick’s Day.

Thanksgiving has penetrated the national consciousness in the U.S. far beyond its influence in Canada, not only because of football – though let’s be honest, that has quite a bit to do with it – but because in Canada Thanksgiving is associated with Anglo-Protestantism. It is not understood to be a genuinely ecumenical holiday because it retains too much of the particular character of Protestant Christianity. The many successes of Thanksgiving in the US where even non-religionists take a moment to reflect before gorging on Turkey is largely due to the secular flavor of the holiday.

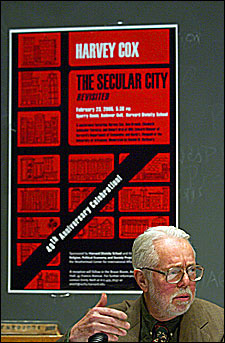

Decades ago, a fellow named Harvey Cox wrote a book about secularism in American culture that made a very interesting claim. In The Secular City Cox’s contention was that the rampant secularism in American cities in the 1960s should be understood as the ultimate triumph of the Christian Gospel, not its rebuttal. His point was that the breaking down of ethnic, religious, racial and economic boundaries between people in large multicultural centers of population, a cultural shift that accompanied the disappearance of engrained denominational and hidebound doctrinal distinctions, this breakdown is the ultimate result of the unifying logic of the Gospel that works to make sisters and brothers of all of God’s children.

Looking back over the decades, many of Cox’s central claims about the triumph of secular political models and the disappearance of organized religion from public life have proven premature at best. However, I want to ask a follow-up question: can we not see in Cox’s thesis a contention regarding the benefits of secularism in city life that parallels our observations about the secularization of many North American holidays? Can we see the cultural shift toward a more secular popular understanding of many of our traditional religious holidays as a culmination rather than a refutation of the Gospel.

This may sound strange at first because I’m suggesting that the less obviously Christian a holiday becomes 1) the less chance there is for the holiday to become an excuse for simple tribalism, 2) the wider the range of possible participants becomes and 3) the better opportunity Christians have for making room within the general uproar of a holiday season for deeper, more reflective, determinate Christian practices.

In closing, I’ll risk a metaphor: Imagine a holiday season to be something like a huge buffet. As the choices at the buffet increase, more people are drawn to take a plate and have a meal, and the entire meal becomes less associated with only a particular group. This does not, however, mean that you and your family with your own plates have to eat some of everything. You are free to concentrate your efforts on only the green leafy veg. or the meat and potatoes. The expanded options encourage wider participation and enlarge the meal. It’s a win for everyone! You get to have the particular and special meal that you want, but you can sit beside and share a conversation with someone whose plate is piled high with curly fries and chess pie.