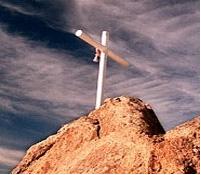

Atop Sunrise Rock in the Mojave National Preserve stands a white cross. The cross was originally erected by Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) in 1934 in order to memorialize the fallen American soldiers of World War I. In 1999 a request was made to place a Buddhist memorial alongside the cross. The National Parks Service rejected the request on the grounds “that federal law prohibits private parties from installing memorials and other permanent displays on federal property without authorization.”

In light of this decision, the National Park Service declared that the cross would be removed as well. This 1999 decision sparked a lawsuit that is now being heard before the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of Salazar v. Buono. At the heart of the case lies a question about the “Establishment Clause” of the Constitution, that is, the separation between church and state. Does the presence of a religious symbol on public land represent governmental support for a particular religion? Jesse Merriam’s article “Salazar v. Buono: Can Government Give One Religion’s Symbol Prominence in a Public Park?” provides an accessible overview of this pertinent case.

Ken Salazar, the current secretary of the Department of the Interior, is arguing two central points before the Supreme Court. Salazar’s first point challenges the right of Frank Buono, former Assistant Superintendent of the Mojave National Preserve, to file the lawsuit in the first place. Salazar argues that Buono was not directly injured or insulted by the presence of the cross or the rejected Buddhist memorial. Since one must be able to show direct injury to have a legitimate federal case, Salazar argues the case is foundationally illegitimate. The second point of Salazar’s argument increases in complexity because it is grounded in events following the National Park’s 1999 decision. In 2003, the land surrounding the cross was transferred to the VFW. Given that the VFW is a private organization, the conflict over the governmental support of religion has been alleviated.

Frank Buono’s case also rests on two central points. The first point responds to Salazar’s charge that Buono lacks the right to file suit. Buono argues for injury since the presence of the cross and the absence of the Buddhist memorial represent governmental support of one religion over another which threatens his constitutional liberties.

Buono’s second point revolves around the transfer of the land to the VFW, but introduces another twist in the case. In 2002 Congress determined that the Mojave cross was a national memorial. This was a distinguished designation since there are only 45 national memorials in the United States. Buono argues that this designation illustrates governmental favor for one religion due to the absence of other religions’ symbols. Even though the land has been transferred to the private VFW, the governmental designation has not been repealed; thus, the Establishment Clause is endangered.

Merriam’s article concludes with a helpful summary of the potential implications of Salazar v. Buono. If the Court determines that Buono does not have the right to bring suit, it will likely become more difficult for individuals to prove injury in respect to the presence of religious symbols on public property. If the Court rules in favor of Buono’s point that the Mojave cross threatens the Establishment Clause, then the government would need to remove lone religious symbols appearing on publicly owned properties. If the Court rules against this point, then there is a danger that governmental support may be lent to one religious group over another. By nature, Supreme Court cases involve complicated and weighty issues. Fortunately, Merriam’s article clarifies the arguments and draws out the possible ramifications of the Court’s pending decision.

Links:

Read Jessie Merriam’s article.