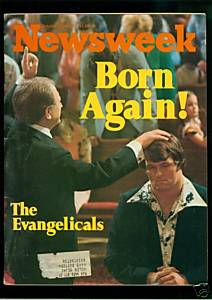

I spent several eye opening hours in the library this week doing some personal research and tracking down sources for teaching projects. For a while I’d been looking for a particular Newsweek cover article on Evangelicalism and I finally tracked it down. This doesn’t sound like much, but the article was from October 25, 1976. At that time Carter and Ford were making their final push before the November election and I was 8 months old. So as I dug through the microfilm cabinets and enjoyed some journalistic time travel I also managed to make some trenchant observations about 1976.

1) Based on the ads, women love men who have big mustaches and drink J&B.

2) Feathered hair and Marlboros make women hot…also based on ad observation.

3) 33 years (about as long as Jesus lived) after Newsweek declared 1976 the “Year of the Evangelical,” certain key problems still plague us. The descriptive phrase that jumped out at me described Evangelical writings as “not a call to Christian servanthood, but an upbeat stress on what God’s power can do for you.”

I love Evangelical churches and I love that they “work,” but I wish we could be more critical about what “working” means. Works for who? Works to what end? Works at what cost?

One of the real strengths of Evangelicalism (and I know this from experience having worked in both Evangelical and non-Evangelical Protestant contexts) is its laser-like focus on whether or not what we are doing is “working.” Seldom is there much reliance on past forms for their own sake. In fact, one of the marks of Evangelicalism might very well be its constant awareness of the need to stay relevant amid the changing tides of fashion and technology even while delivering the same Gospel.

If the old tunes aren’t working, find new tunes. If the old building is too small, build another one. If the way we did it last year isn’t working this year, find a new way. If a church ain’t growing, it’s dying! This strategy/attitude keeps the clergy and the congregants on their feet and, in the best case scenario, keeps us all vigilant against the creeping decay of complacency and institutional inertia. I’ll call this phenomenon “Evangelical Pragmatism.” At times it can feel as if we are Christian toddlers, running about the house in search of constant novelty. But many of us recognize that this is a price we must pay for continual vibrancy – onward Christian soldiers. There is another danger here, however, and it has to do with overlooking the very thing that frequently seems to be so obvious. What does it really mean to have a church that “works?”

Allow me to give voice to the operative definition of “working” in many Evangelical contexts – and please forgive me if, for the sake of making a point, I put the issue in the crassest light. A church that works is growing i.e. attracting middle class families in their prime earning years. A church that works just moved into, is moving into, or plans to move into a new building with the latest sound system. A church that works is full of young people and its halls and pews aren’t clogged with oldsters. A church that works leaves its congregants feeling closer to God and more satisfied with their spiritual lives, marriages, and place in the world. A church that works is constantly hiring and welcoming new members. A church that works has warm cookies at coffee hour. (Snuck that last one by you didn’t I!)

So in the spirit of Evangelical Pragmatism many churches are constantly asking, “What can we do for you? How can we help you tap into God’s power for your life?” This is a good thing. But how easy it is to forget that we the congregants ARE THE CHURCH. If we’re the church, then forget about whether brown is the new black, who’s the new “you.” Who should we be seeking to serve and who should we be trying to connect with God’s power? Are we the church not intended to be the embodiment of that power? Are we not here to work as ministers, the very hands of God in the world? What then is a church that works?

Look again at these words from 1976 – “not a call to Christian servanthood, but an upbeat stress on what God’s power can do for you.” Perhaps we ought to consider that what God’s power can do for us is help us answer the call to Christian servant hood. And so, to paraphrase/botch JFK, ask not what the church can do for you, but what you the church can do for the world.

The point I’m pushing here is a reevaluation of our ends. What are we aiming at when we want a church that works? Too often I think we may aim at a church that is growing numerically and financially, but also a church that is reifying and reinforcing the ideas and ideals that we already possess. When this is the case it is no wonder that we so easily slide into easy conflations between church goals and political goals – when we seek to build churches that serve our own needs is it any wonder that we easily confuse political and ecclesiastical goals. A government of, for and by the people may not be easily distinguished from a church that if of, for and by its congregation.

So let me sum up. Evangelical Pragmatism is good insofar as it keeps us relevant, engaged, and creative. BUT – Evangelical Pragmatism must work hard to avoid simply begging the question. We can be extremely creative in the means we develop to pursue the same old private and limited ends. We need to be equally critical of the ends we pursue i.e. critical of our conception of what it means to have a church that “works.” It would seem that the most important question that we should ask is what a Kingdom vision of what “works” would look like.

What end should the church pursue?

What does it mean to “bear fruit?”

Is my own subjective happiness the standard for knowing whether my faith and church is working of is there a broader standard?

I’m going to hold onto this piece from 1976 for a while. I’ll reread it again in a couple of weeks, because I’m convinced that many of us have spent much of the last 33 years spinning our wheels on the these very questions. We’ve become great problem solvers and I don’t think you could find many plausible voices who would suggest that Evangelicals are not particularly skilled at finding new strategies for pursuing our religious and institutional ends. Give us a goal and we’ll find a way to get there. But are we any better that anyone else at identifying the right goals?