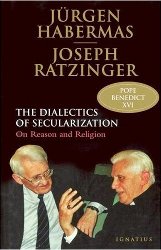

The Dialectics of Secularization. Jürgen Habermas and Joseph Ratzinger. San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2005. 85 pages.

In January of 2004, Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, now Pope Benedict XVI, posed this provoking question to his audience at the Catholic Academy of Bavaria: Is religion “an archaic and dangerous force that builds up false universalisms, thereby leading to intolerance and acts of terrorism” (64)? The context for the question was a debate between himself, then Prefect of the Roman Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and Jürgen Habermas, a liberal, secular philosopher, receiver of the Kyoto Prize for lifetime achievement, and self-proclaimed as “tone-deaf in the religious sphere” (11). The Dialectics of Secularization is a transcript of their dialogue in response to the agreed upon subject: “The Pre-Political Moral Foundations of a Free State”.

In other words, must a constitutionally-defined free state justify its ethical norms with an antecedent, universal claim for truth and, thus, compromise its own claim of a neutral world view? On the other hand, how can any religion which does make universal claims justify those claims in a manifestly plural world without bending towards intolerance, injustice and, in the extreme case, acts of terrorism? One might think Cardinal Ratzinger, staunch defender of Catholicism, would be obliged to answer “no” to his own proposition of religion as an archaic and dangerous force; and one might think that Habermas would defend his own commitment to a neutral, universally accessible reason as the antidote to claims of any revelation antecedent to reason. Instead, however, both men promote the limits of their respective positions, succeeding in the difficult but worthwhile balancing act of criticizing the presumptuous over-reach of their own tradition while still articulating unwavering conviction.

Habermas concedes that free, secular states have arisen, at least in the case of his native Germany, from a “common religious background and a common language” (32); but instead of being overly concerned with the past, Habermas is more concerned with whether such states as they exist now can justify their commitment to neutral, non-religious principles of reason without falling into the safe arms of that which they tried to free themselves from. Can they renew normative presuppositions from their own resources? Yes, he says. The democratic process is legitimate because it depends not on a claim but on the constant, corrective communication between the collective decisions of citizens and legislation which guarantees those citizens basic liberal and political rights. These two partners in the process “the legislating citizens and the law itself” satisfy the secular, democratic conditions of both inclusivity and reason. Therefore, according to Habermas, regardless of whether citizens are themselves motivated by a particular ethic or perceived revelation the liberal state can “satisfy its own need for legitimacy in a self-sufficient manner” (29): its uniting bond is no longer an antecedent norm outside of the democratic process but the “democratic process itself – a communicative praxis…exercised only in common and that has as its ultimate theme the correct understanding of the constitution” (32). Habermas does not claim democracies are perfect or that they eliminate inequality altogether; he simply says that they can maintain legitimacy without having to ground themselves in any singular world-view or metaphysical understanding.

However, he admits, there is a catch. Democracies demand the solidarity and commitment of their citizens to the process itself. And as society has increasingly become a global society beyond the boundaries of particular political systems, and as the global economy is only minimally constrained by the political system, citizens are losing hope in the process itself. There is, currently, no law which can guarantee human rights in the global sphere. Therefore, the secular state is beginning to break apart as people increasingly feel compelled to act in their own self-interest. And the external threat of states and citizens not committed to democracy only increases this de-stabilization, he says. Habermas does not give in at this point, though. He does not say that the secular forces of communicative reason do not work in a global, plural society. He simply says that the forces should be treated “undramatically, as an open, empirical question” (38). And, he also says, reason has its limits and must become aware of them.

First of all, according to Habermas, reason can not claim to know what “may be true or false in the contents of religious traditions” (42). More than acknowledge the existence of religions and respect the possibility of various claims, however, Habermas admits that there is something to learn from religious traditions, something which reason does not provide, something with substance. Religions, he says, have kept alive and continue to reformulate contextual interpretations of redemption, of “salvific exodus from a life that is experienced as empty of salvation” (43); this, he says, is impossible for experts of secular reason alone. What secular society must learn to do with these contextual interpretations is make “the substance of biblical concepts accessible to a general public that also includes those who have other faiths and those who have none” (45). When secular systems can learn to do this, to internalize contributions of religious traditions and to not ignore the individual voices which claim religious convictions, then they can begin the process of having those individuals trust in the democratic process, even if in doing so they have to give up the idea of a post-metaphysical society in favor of a post-secular one. For the uniting bond of the secular democratic process depends on the faith and commitment of the people to that process.

Ratzinger, for his part, did not champion his own religion or any metaphysical basis as the legitimating force behind western democracies. Neither, however, did he agree that the secular forces of communicative reason should be treated as an open, empirical question: he agrees with Habermas that secular reason and religious convictions should learn from each other but he also demands, in a way, something more than that, something more active, something as revolutionary to secular democracies as secular democracies were to the European churches.

Ratzinger opens his discussion with a brief analysis on the dynamics of power and law. The law, he says, cannot be the arm of the strong; for law is the only thing built strong enough to oppose those with power. It offers strength to those that are weak, it is the antithesis of violence because the true function of the law is equality for all. Law needs a just, legitimating force, according to Ratzinger, because “revolt against the law will always arise when law itself appears to be no longer an expression of a justice that is at the service of all but…the product of arbitrariness and legislative arrogance” (58). Democratic systems of law, he says, are now under suspicion, not because they have never had legitimating force but because those veteran forces are no longer suited to what he sees are new vulnerabilities in society. The pace of global interconnectedness is quickening; world views are colliding at an alarming rate and with those collisions comes a fear of losing what is most precious to each world view. But where Habermas suggested that people of religious world views can come to trust in the protection of secular systems, Ratzinger suggests that those systems of reason may now be defunct.

This brings Ratzinger to his question of whether religion is to be blamed for the acts of terrorism and intolerance that occur when conflicting world views collide. He does not answer this question directly, he leaves it open and, in a way, admits that it is often true. But he also takes this question and directs it at reason: might reason also be a dangerous, archaic force, responsible for intolerance and acts of terror? Reason has taken humanity not just as far as the atomic bomb, but even further, to the point where “man is now capable of making human beings, of producing them in test tubes…man [has become] a product…he is no longer a gift” (65). One could debate whether selective breeding of human beings is a new phenomenon or not, but it is hard to argue with Ratzinger’s point that the pace of the effort is out of control, that the sense of life being a gift is disappearing. He is right, then, when he asks: “Does this then mean that it is reason that ought to be placed under guardianship? But by what or by whom?” (66)

His suggestion is not that religion can once again rear its head as the public savior of a process gone astray. Yet neither does he believe that the answers are found in a debate between secular reason and religion, specifically his religion or even western religions; Ratzinger goes further than Habermas and suggests that the classic debate between a “neutral” secular reason and a Christian-dominated world view in the west is not even a universal debate. Western rationality and universal claims of Christian revelation must both be called into question. Both are global in their reach but are “de facto not universal….[Western culture] as a whole comes up against its limitations when it attempts to demonstrate itself” (75-76). What does Ratzinger suggest, then? He admits that there are pathologies in religion, but demands a similar admission from secular reason. He agrees with Habermas that secular reason and the Christian religion (specifically) need to learn from each other. He also believes that they need to be willing to learn from ideas and commitments foreign to them both. This learning process has to be more than something abstract though; it has to involve something that does not yet exist. Ratzinger does not propose much in the way of what that something could be but he offers hints as to what he thinks it needs to subject itself to. Society, he says, has focused its recent attempts of justice and equality on the broadening protection of human rights. To learn from each other, maintain individual convictions and create an effective, legitimating force, suggests Ratzinger, human rights need to be coupled with some sort of human obligations.

Both Ratzinger and Habermas have radically different world views – any agreement on their part does not betray that fact or try to cover it up for the sake of a quiet tolerance of the other. In their dialogue, however, they each find a way to engage in relationship with the other’s world view without neutralizing, softening or making their own view seem illegitimate. This offers hope to readers who are engaged in either a similar debate with peers or even in an internal debate within their own traditions. But readers should not be deceived: the book is not an easy read and neither was the process that enabled Ratzinger or Habermas to articulate their convictions an easy one. A lifetime of thoughtful work, disciplined study and unique life-experience characterizes both men. The book is a lesson of patient energy that is useful as a tool for any potentially explosive dialogue. What is interesting, though, is that both Ratzinger and Habermas expressed a willing hope for something that neither of them yet experience as manifest. Habermas is asking people to commit to the ideal of a political process that can only become ideal when people commit to it – there has to be an element of trust involved, trust in something that does not yet even exist. And Ratzinger is suggesting that what has brought history this far has not been something stagnant and, in fact, cannot be stagnant for the world to continue to hang together. Inherent in the specific positions they propose is their mutual commitment to something new, and their simultaneous commitment to continually redeem what is old.

Sally Paddock

Boston University