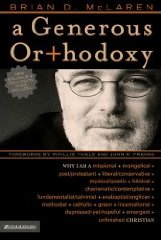

McLaren, Brian. Generous Orthodoxy: why I am a missional, evangelical, post/Protestant, liberal/conservative, mystical/poetic, biblical, charismatic/contemplative, Fundamentalist/Calvinist, Anabaptist/Anglican, Methodist, Catholic, Green, incarnational, depressed-yet-hopeful, emergent, unfinished Christian. El Cajon, CA: Youth Specialties, 2004.

Brian McLaren, one of the early leaders of the recent emergent church movement, wrote Generous Orthodoxy to convey his understanding of the Christian message. He accomplishes this through a confessional faith story of how has interacted with Jesus Christ and Christianity throughout his life. McLaren weaves an auto-biographical narration of his life into a declaration about the way he believes Church should be. His own faith was formed by being uncomfortable with any one brand of Christianity. He incorporates experiences of various denominations within Christianity – from the far right to liberal churches and many in between – into his understanding of his own faith. As he touches each of these types of Christianity he conveys a distinctive understanding of Jesus Christ that draws on elements collected from each of those variations of Christianity.

The term “generous orthodoxy” is paradoxical in nature. “Orthodoxy” means right thinking. How can one be generous in right thinking? McLaren believes that the various denominations and movements all have it right in some ways and all have it wrong in other ways. There is something within each one of them that speaks to him. He seeks to take the best of each those ways of thinking about God and leave the worst of them behind. Throughout the book there remains an intentional tension between right thinking, at least the way McLaren sees it, and the generous aspect of McLaren’s theology. “This generous orthodoxy does not mean a simple merging, mixing, conflating, or reconciling of the two schools of thought (liberalism and evangelicalism), though. Rather it disagrees with both regarding the view of certainty and knowledge which liberals and evangelicals hold in common.” (24)

An obvious critique of McLaren’s theology is that it falls prey to the dark side of pluralism by embracing relativism free from any standards, and he acknowledges this critique. However he intentionally tries to live within the tension that results from acknowledging partial wisdom in many parts of the church. As he says, “exclusive religion says, ‘We’re in, you’re out.’ While universalist religion reacts and says, ‘everyone’s in’… Magnanimous apathy may be better than narrow antipathy often associated with exclusive religion, but I think we need a better alternative.” (109) McLaren desires a Christianity whose value is judged in part “based on the benefits it brings to its non-adherents.” (111) His missional calling is that he is “blessed in this life to be a blessing to everyone on earth.” (113) McLaren avoids confronting the exclusive claims of the bible with this pronouncement.

The bulk of the book shows how McLaren navigates through a variety of groups within Christianity. He tries to take the best they have to offer and leave behind the worst. Sometimes this works well, other times not so much. As one can see from the title of the book the list of groups that McLaren uses to inform his faith is long (and he admits it could be longer). There is no simple way to summarize each of these groups. Therefore I will choose two of the groups to discuss and analyze. I will choose the group that I thought he did the worst job incorporating into his personal theology and also the one I thought he handled best.

The problem when you try to leave the worst behind in a religion is that you often change the religion dramatically. The best example of this appears in the chapter “Why I am a Fundamentalist/Calvinist.” McLaren proposes “a slight revision in the old acrostic (TULIP) for Reforming Reformed Christians.” (195) Traditionally TULIP stands for total depravity, unconditional election, limited atonement, irresistible grace, and perseverance of the saints. McLaren wants the “slight” change that lets TULIP stand for triune love, unselfish election, limitless reconciliation, inspiring grace, and passionate saints. If this change were to happen the reformed tradition would radically change its theology. Almost by definition unconditional election is selfish (as is election in general), as it decides “who’s in” and “who’s out”. McLaren cannot interchange the words unconditional and unselfish and pretend that it doesn’t change the doctrine of the church. He may “hope that these are already in fact the true colors of the best of the Reformed tradition”, but perhaps the traditional TULIP is the color of the Reformed tradition.

In other places McLaren’s critique of a faith tradition offers some understanding that does not seek to alter the tradition in a fundamental way. Being a Methodist, I agree with the current state of Methodism that McLaren critiques in the book. The imagery that McLaren uses of people pulling and pushing each other up a mountain conveys how Methodism worked in its early stages. (It’s also how it best works today.) However, at some point many Methodists reached a plateau and looked down upon those that had not made it with them. They ceased helping each other up the mountain. McLaren hopes (and I join him in this hope) that “discipleship as the process of reaching ahead with one hand to find the hand of a mentor a few steps up the hill, while reaching back with the other to help the next brother or sister in line who is also on the upward path of discipleship.” (220)

McLaren’s Generous Orthodoxy is essentially an account of one man’s struggle with the many different forms of Christianity that he has encountered in his lifetime. He seeks a Christianity that takes the best of all these encounters, and leaves the worst of them behind. In the case of Methodism, this works well. However, there are times this does not work as well, as with Calvinism, because what emerges is no longer recognizably Calvinism. Ultimately, if “orthodoxy isn’t a list of correct doctrines, but rather the doxa in orthodoxy means ‘thinking’ or ‘opinion,’ then the lifelong pursuit of expanding thinking and deepening broadening opinions about God sounds like a delight, a joy.” (294) Brian McLaren’s faith journey and orthodoxy is evidently not yet finished. Perhaps the journey is meant to be unfinished.

Kenneth Mantler

Boston University